RPG Maker Dungeon #6: Pangea's Error

Link: https://vextro.itch.io/gardens-of-vextro Play in browser: https://tunditur-unda.itch.io/pangea

Originally published February 26th 2023

I was listening to an episode of a podcast last week when I heard something quite bizarre. A listener posed a question to the hosts asking, "what are your favorite short RPGs, for folks who don't have much time?" The hosts gave some good answers, such as Crimson Shroud (soon to be lost with the closure of the 3DS eShop!) and The Longest Five Minutes. But then one of the hosts said that by their nature, the best RPGs are not short. RPGs are about mechanics, and mechanics demand length to fully explore. A game without deep mechanics, therefore, is not worthy of being called an RPG.

What does it mean to be an RPG? Take Chrono Trigger, which the hosts in that same episode recommended to anybody wanting to learn what RPGs are about. Chrono Trigger is a thoughtful, aesthetically fantastic adventure game that plays like the best comic that never ran in Shonen Jump. Its mechanics are also about as deep as a puddle. The characters learn a handful of skills apiece and travel a straightforward path to the finish. The game's difficulty is calibrated so that its spiciest encounters prompt you to take a breath and reassess rather than turn off the console. It is a game that anybody of a certain age can play and finish without any problems. Just what you'd expect from Yuji Horii, one of several illustrious designers from that time who contributed to the game.

A certain kind of fan may look at Chrono Trigger and say, this is not a true RPG. They might point instead to a computer RPG like Morrowind, which allows the player to buy their own house and fill it with whatever they like. Or perhaps they'd prefer Romancing SaGa 2, an extraordinarily difficult game that demands careful study to make it to the final boss. The truth is, though, these are all just different kinds of RPGs, with their own priorities. Morrowind simulates a world. Romancing SaGa 2 rebuilds the adventure games of its time from the inside out. Chrono Trigger is a blockbuster that takes the player through many exciting setpieces. Each approach has its adherents, although some are certainly more popular than others.

If you really want to understand RPGs, you should be playing games made in hobbyist engines. RPG Maker, OHRRPGCE and Wolf RPG Editor are three that are well-known. "But the majority of games made in this engine are trash!" you might say. But "understanding RPGs" has nothing to do with "understanding good RPGs." (Plus, many of them are great.) What makes these sorts of indie games valuable is the freedom that comes with making art at a small and idiosyncratic scale. Any one developer might choose to focus on fighting, or exploration, or aesthetics. This inevitably means compromise in other respects, like making use of existing resources or ripped music. Still, you know when you pick one of these games that you're playing something direct from the heart. A game that makes use of its technical and logistical limitations to create an experience that can't be found anywhere else.

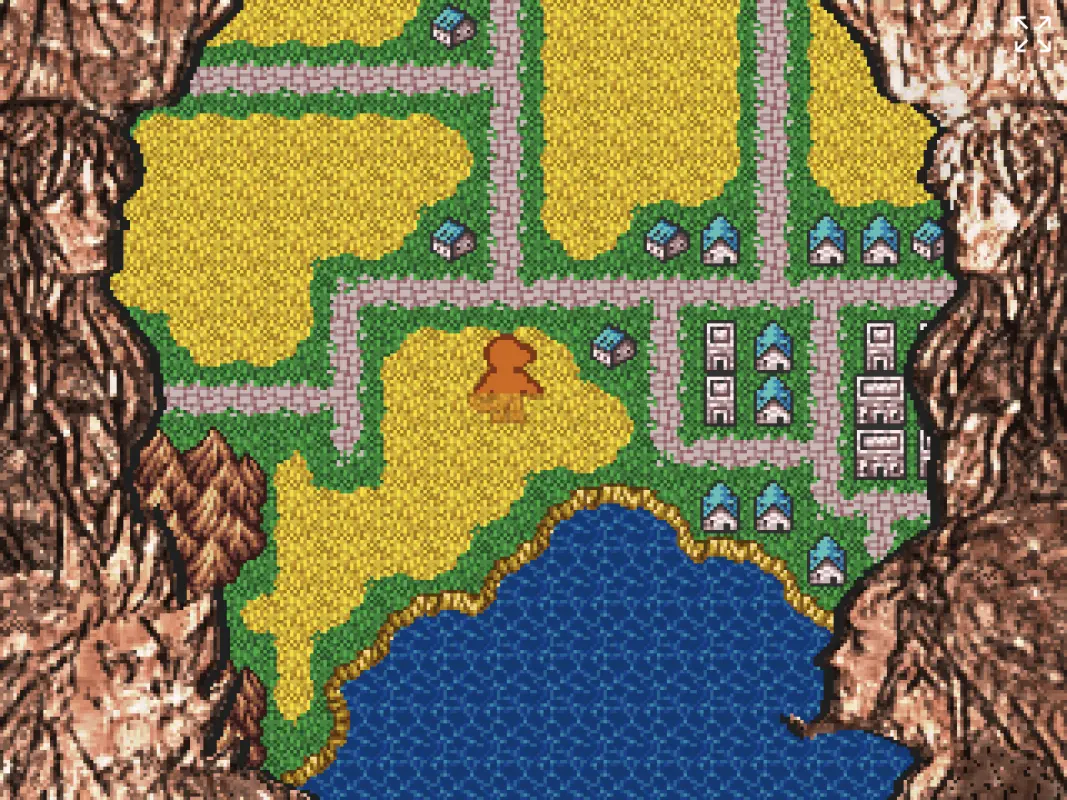

Pangea's Error is one of eight games made as part of the Gardens of Vextro anthology project. (I have not yet played them all, but I can vouch for their quality based on the folks involved.) You play as an orange lizard named Erato wandering a big RPG map. Erato can only walk forwards, not backwards. You turn with the left and right arrow keys, and when you turn the entire screen swings in that direction. (RPG fans may recognize this trick from Falcom's RPG Brandish.) A giant border featuring four faces obscures the left and right sides of the screen. The music is eerie and nostalgic, a half-remembered scrap of detritus left over from an old lost RPG. A gleaming spot just ahead of Erato reveals a scrap of narrative and a named sword. Other swords dot the map, and finding each of them is the only direct window you are given into the workings of the world. Some are recovered from long-lost ruins, others are given to you by local inhabitants or travelers. They do not make Erato any more powerful, but it is nice to collect them.

Playing Pangea's Error makes me feel carsick. Turning the whole screen in one direction, then another, is dizzying. The game never lets you see the broader world map. You must rely on visual tells and landmarks: the color of the buildings and the mountains, dead-ends and valleys. Grass gives way to snow and then to desert. Navigating the mountains means contorting Erato through narrow rocky corridors. Houses and castles dot the map but unless there is a gleaming spot there, Erato cannot visit them. It is a lonely, disorienting existence, but that just makes those few glimpses of community that much more memorable.

Playing Pangea's Error reminds me very much of Dragon Quest Monsters, a game where the hero travels through randomly generated monster dungeons to bittersweet chiptunes (composed by a bigot.) The impermanence of the game's abstracted world, combined with the melancholy of its soundtrack, has stuck in my memory ever since. The more RPGs of this type you play, though, the more familiar they become. Games transform from illusory spaces full of possibility to checkboxes of tropes. Pangea's Error defamiliarizes the genre, asking the player to reexamine what they've taken for granted. What does it mean to move in an RPG world? Can difficulty exist outside of numbers or systems? Perhaps Pangea's Error could work with more traditional navigation, but it would be a different game. The friction of the movement forces the player to let down their guard, and be mindful about moving through space.

I'll admit here that I'm friends with sraeka, the game's developer. sraeka has a synesthetic appreciation for the aesthetic trappings of roleplaying games that I always appreciate. The particular design of the menus. The fuzz of the music. The sparse dialogue. Pangea's Error is not necessarily complicated, but it is a game that was clearly pieced together with careful thought and an artist's eye. If the boundary between grass to snow in the game world did not inspire the player to reflect on the possible connections between these two spaces, Pangea's Error would fail. It succeeds only because it was made with intention and the lessons of past experience.

I have not yet finished Pangea's Error. I found nine swords and have explored a few different areas. With no world map to serve as a reference point and no idea what the end of the game might look like, I've found myself retracing previous steps en route to new lands. That the game still makes me feel nauseous means I've put it down for now. Perhaps I'll finish it one day. Still, the feeling of it is something special. Pangea's Error is more than just a "good game." In fact, whether it is a good or bad game is irrelevant. What matters is that it transformed a world that had become familiar to me into something new and strange. I thought that was impossible, but never underestimate videogames.

Pangea's Error is just one of many short games of its type that play with the rules of RPGs. FRANKEN and Southern Cross are two recent examples. So are the VIPRPG titles, which dedicated fan Kastel has written about here. Some of these games are very small traditional RPGs, others adapt the aesthetics or ideas. A few take the RPG Maker engine and its brethren into unfamiliar territory, like board games or management sims. These games aren't wholly unknown. Edwin Evans-Thirwell wrote a great article about a few of them on Eurogamer. But the games press as a whole tends to ignore them.

How could it be that a podcast that specializes in RPGs doesn't know anything about these games? It's not because of malevolence or laziness. The truth is that there are so many games being made right now that it is tough to keep track of them all. The games that are talked about often come from a proven publisher, have a marketing budget or are just lucky. The rest are lost in a sea of competing alternatives, ripe for rediscovery by dedicated communities of hobbyists. As much as folks like to say that they "want shorter games with worse graphics made by people who work less and I'm not kidding," what they mean a lot of the time is that they want to play games of this type made by people they already know. It's tough to take a leap of faith when time, as a player or a critic, is finite.

My advice is to seek out critics and communities with their own unique tastes. Instead of buying whatever new game folks are talking about, why not go digging for a solo title on itch? Why not try out something new, like a visual novel or a game made in Megazeux? There are buried treasures everywhere, and while many will not be to your taste there's at least a few that might do what Pangea's Error did for me: punch a hole through the clouds so that the stars are briefly visible. And if you prefer long games, well, some of these games are really long too. Everything has its season.